An Atmosphere of One’s Own

by Jared Michael Lowe

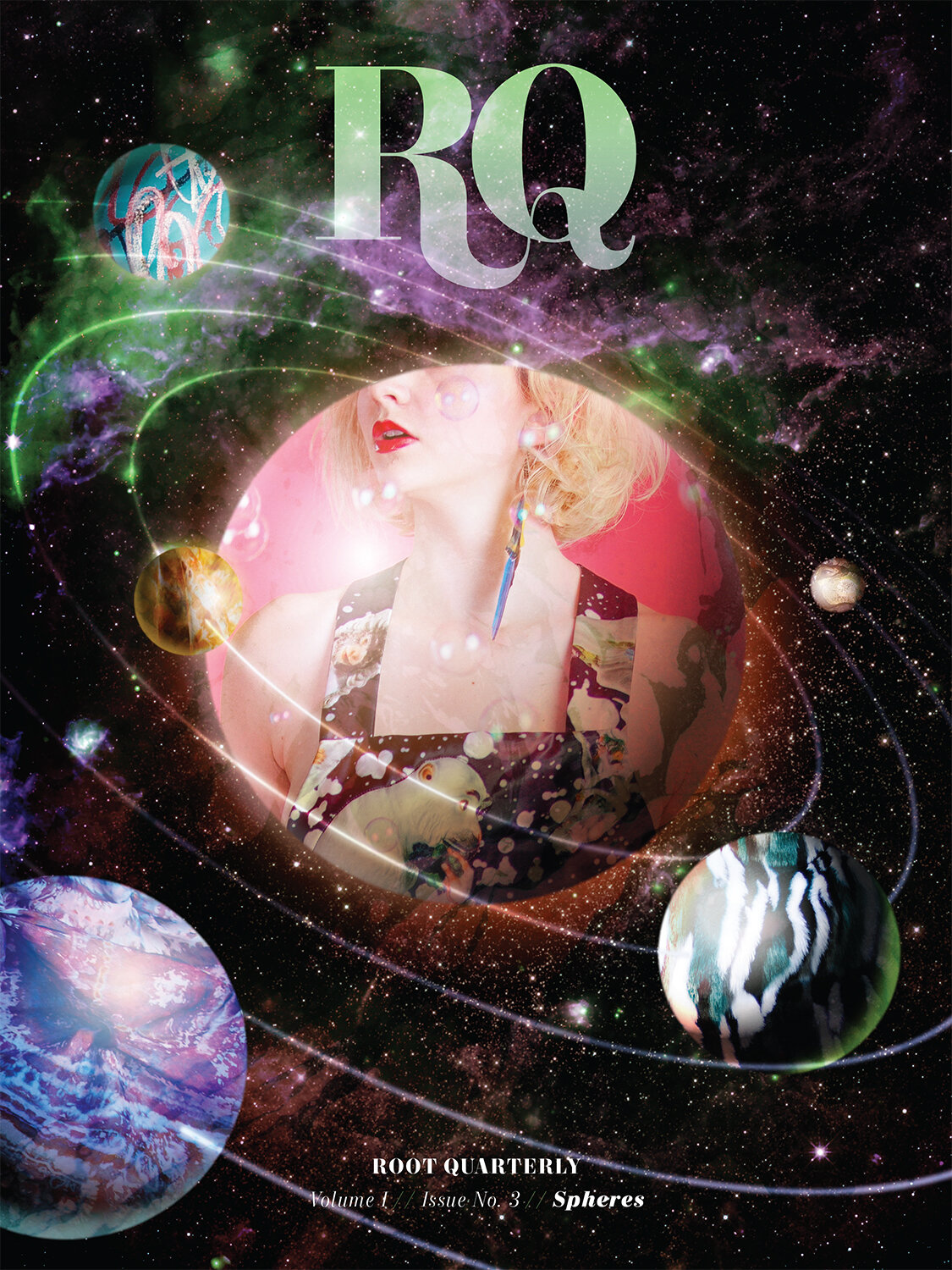

This article originally appeared in RQ Vol. 1 // Issue Three: SPHERES, Winter 2019. Purchase a copy and subscribe to the magazine here.

“Creativity is my oxygen,” says fashion designer and emerging couturier Nancy Volpe Beringer, 65. She reclines comfortably across from me on a white couch as we sit together in her study, which now operates as a makeshift showroom. Around us are rows and rows of clothing racks lined with metallic sheaths, glitzy gowns, kimonos, and coats of various kinds—from ethereal hand-dyed numbers to eye-popping pieces made from surrealist patterns.

It’s the den and zen of Volpe Beringer’s creativity, a cosmic jungle of artistic inspiration where smatterings of pinks, emeralds, and canaries sing alongside the murmuring textures of heavy wool, organza, fur, and fringe. In this sartorial paradise, she imagines fun and fearless confections.

Moments into our interview, she shows me pieces of her collection that she defines as “wearable art,” clothing that is made to be expressive clothing with which to adorn oneself. It’s a technique that Volpe Beringer has become known for, especially after dressing Philadelphia rapper Tierra Whack earlier this year for the 61st annual Grammy Awards. Whack, in the rainbow-hued, floor-length faux-fur coat and matching gown, was described as “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat” by The Philadelphia Inquirer’s lifestyle columnist, Elizabeth Wellington. Soon after, Volpe Beringer scored a spot on the massively popular show Project Runway.

Her newfound career, which she bravely pivoted to at the age of 58, is as thrilling as it is unlikely, and has launched her into new spheres. But throughout her life, she has followed the same thread. “All that I’ve been doing, all that I know how to do,” she says, “is to create.”

A Star is Born: Patterning a Life in Style

Volpe Beringer was very shy as a child. “I faded in the background,” she tells me. She is the middle child of six, born in Philadelphia and raised in Levittown in a traditional suburban home. During summer camp, when she was 12, she took two courses: public speaking (to get over her shyness) and sewing. She found that she loved to sew. “It was a way to express my creativity, and I gravitated toward the craftsmanship of it,” she says. At 13, she put an ad in the paper to solicit work mending, tailoring, and ironing clothes. Her family didn’t have much money, and she would use whatever she had to buy fabric and make her own clothes as well. Her grandmother worked in Gimbels in Center City, and Volpe Beringer remembers taking the train into the city to visit her. Roaming Philadelphia’s bridal and dress shops, she’d find inspiration in the store windows and sketch prom dress designs on a pad of paper.

She recalls making a full-length maxi coat that was fur lined with matching hot pants. “It was really out there, but it was the ’60s, so everything was out there,” she laughs. It’s clear from the image of this look that Volpe Beringer’s play on silhouettes was an early aesthetic, as indicated by her collections now. “You know, I never thought of that,” she says. “I just knew that I loved to sew and wanted to create whatever was in my head.”

While she’s now back to designing, she lived quite a different life a decade ago. She was at the peak of a successful career in education, the recipient of a much sought after job promotion, recently married, and watching two sons from a previous relationship graduate college and embark on their careers. The once single mother who had held down four or five jobs at a time to support her family now seemed settled and comfortable—but she felt creatively stifled.

“I felt like my oxygen was being siphoned off after receiving the promotion. I wasn’t creating and I knew that I needed to change that,” she tells me. She wanted to break out of where she was, break out of patterns of bad personal and business experiences, some of which were bullying and abusive. So, on one sleepless night, she asked herself, What would I want to learn if I was young again?

She reflected on her experience fabric shopping in Philadelphia as a child, and on the business successes of her two sons. The answer and inspiration came quickly: Design.

After briefly considering fashion programs in New York, she found Drexel University’s internationally acclaimed Westphal College of Media Arts and Design. “I loved it,” she says. “I forgot that I looked different. I would be reminded when I had a critique, when the students would introduce themselves to me, because they thought I was a professor. I felt very comfortable with my classmates.” They happily learned from each other, she says.

Though she was having the time of her life, she endured 80- to 100-hour school weeks, and, midway through her program, she had to deal with the onset of painful arthritis, something she still experiences today. She recognizes her age was a factor in her struggle with the workload. But in the classroom, she also saw that she had a secret weapon: Experience.

“I was able to appreciate the process of getting to the runway senior year and, more importantly, enjoying it.” She went on, “In today’s world, we are being accustomed to instant gratification, information, and results. Everything is so immediate, like it is right there. Because of my professional background and age, it helped with my understanding that design is a process; it doesn’t happen the first time or the second.”

After graduating, she won a design award from Philadelphia fashion icon Joan Shepp and found herself designing for Shepp’s concept shop. Her evening wear collection was featured in its iconic holiday window alongside pieces from fashion’s heavy hitters, such as Dries Van Noten, Maison Margiela, and Comme des Garçon.

“It was the ultimate pinch-me moment for me at that time, to see my collection in the window alongside pieces from storied fashion houses,” she says. “And they were holding up well.” It was also how Whack found her designs.

“Tierra was shopping with her mother in Joan Shepp, and she saw the multi-hued floor-length faux-fur coat. She bought it, and the people at Joan Shepp told me about it, so I sent her a thank you note as a DM to her on Instagram,” Volpe Beringer says. “We followed each other then, and then talked. She told me she was thinking of wearing it to the Grammys. I became very excited.”

Knowing that Whack would need a dress to go under the coat, she gave her one of her designs, and then boarded a plane to Los Angeles to help dress the burgeoning rapper for the show. She remembers the night as “crazy,” and couldn’t contain her excitement when she saw Whack wearing her full ensemble.

“I literally jumped up and screamed,” Volpe Beringer recalls, visibly excited as the memory comes back to her. “I was with Tierra’s hair and makeup people, and we all jumped up and screamed. It’s one thing to see your creation before it walks out the door; it’s another to see it on television.”

Whack, who was nominated for her first ever Grammy for best music video for “Mumbo Jumbo,” eventually lost to Childish Gambino’s “This Is America,” but the look would become a viral sensation and was one of three designs to be featured in The New York Times. Volpe Beringer was then invited to participate in Philly Fashion Week.

Then came the bid to be a contestant on the upcoming season of Project Runway.

“It started as a fantasy,” Volpe Beringer recalls. “When the first season of Project Runway premiered, I was 50, and I remember watching the show, like so many, and thinking quietly to myself, ‘Wow, what if I was on the show? What if with your love of sewing, you actually went and studied it, and pursued your love of fashion?’ I never told anybody.”

After her first unsuccessful bid to be on the show, she went to Central Saint Martins, the acclaimed arts and design college that helped shape the careers of fashion stars such as Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, and Stella McCartney; she took an intense online course in draping; she was mentored by a published fashion author on couture. While celebrating her wedding anniversary in Florida—“I was studying a pattern-making book at the time,” she recounts—she got the call finding out she would be on its eighteenth season. She is their oldest-ever contestant.

I asked her if she recognized a pattern in that instant. “For me it’s been to walk into situations that I’ve never been in and having the determination to come out and move forward. I don’t go backward. I move forward. It wasn’t just about being back in a classroom or learning a new skill, but always being vulnerable and putting myself out there.”

And Volpe Beringer is still shopping for fabric in Philadelphia like she did when she was younger. “When I walk into a fabric store, I see a pattern and all I know is that I don’t want to tear it up,” she says. Instead, she wants to find a way to make the pattern fit a body. In her studio, she pulls out a Salvador Dali panel of fabric. It’s cerulean blue with many of Dali’s talismans: melting clocks, enlarged eyes, coyotes, a desert landscape. She shares with me that when she shops, she doesn’t look for a specific design. The fabric she finds influences her design choice. “We—I say we, it sounds like I have all these people helping me, but it’s just me and my fabric—we design together.”

We’ve spoken for hours, which feels like minutes, surrounded by fabulous frocks and the kind of whimsy one would encounter if traveling through a fairy tale. Though her life has been far from one, Volpe Beringer is living one now. At the crux of our conversation is pondering the notion of how personal revolutions prepare us for the roles or the worlds we later walk through. When I ask her if, at 12, she thought she would be designing now, she says emphatically, “No—not in a million years. I never thought I would be a designer right now, not when I was 12. This is a full-circle moment.”

Most recently, she has used her platform to do her most rewarding work: teaching refugee women sewing, textile, and business skills for Refugee Women’s Textile Cooperative. She has used her fashions to support many organizations throughout the city and has designed for local charitable organizations such as Women Organized Against Rape, the Salvation Army, Flyers Charities, and several others.

When I ask her what she hopes is next for her, she goes back to her oxygen and the atmosphere she thrives in. “I just want to continue to create clothing,” she says, “that gives me a platform to make the world a better place.”

This article originally appeared in RQ Vol. 1 // Issue Three: SPHERES, Winter 2019. Purchase a copy and subscribe to the magazine here.

Jared Michael Lowe is a lifestyle writer, communications strategist, and creative consultant. He’s led social media strategy and engagement for WHYY, the University of Pennsylvania, and a host of media, academic, and cultural arts organizations. His editorial work has appeared on NBC News and in Cosmopolitan, Teen Vogue, The Huffington Post, and Ebony magazine. He currently serves as the communications manager at the Sustainable Business Network.